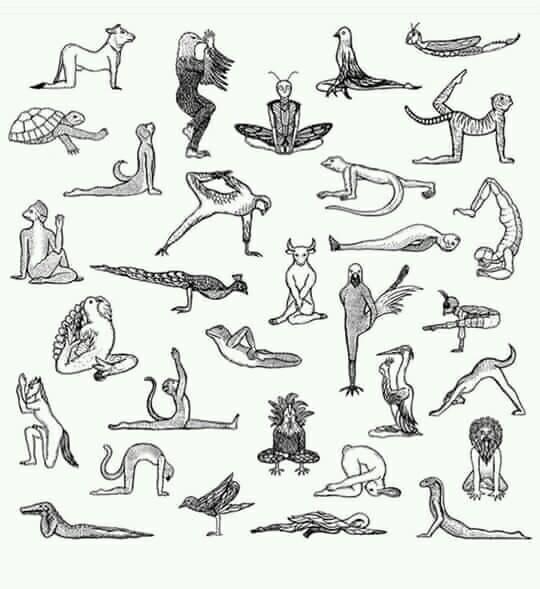

These yoga postures are called “asanas,” which means “a posture held with coordinated breathing.” Ancient forest dwelling yogis named the asanas after animals in their natural postures. The purpose of yoga asanas are to help one advance in meditation. Their practice brings health, longevity and strength to the body but their primary purpose is to help one spiritually by aiding deep concentration in meditation.

Asanas were not designed for Barbies in yoga salons but for serious and dedicated yogis seeking spiritual liberation and working to refine human nature at the individual and collective levels of the species. They cause one to evolve physically, psychologically, and spiritually. Liberating tensions and energetic blockages in the body and redirecting the released prana (vital energy) upward into the brain causes new currents of activity. First, the prana creates this new channel or groove in the subtle body and then later the brain begins to change and mimic the new energetic patterns created by the prana by creating more complex neural connections. However, the mind must be able to assimilate these changes, and so it is therefore necessary to deeply understand what yoga is designed for.

Changes in both the individual and collective minds must be made gradually, with full awareness and an assessment of the forces required to combat the inertia, or force resisting this evolution. Just try forcing your prana, or vital energy, above with the blind will of the ego. Later, prana reacts and causes the mind to dive downward with the same intensity. This explains why there is always a scandal with commercial yoga.

Yoga asanas like “the flying lotus” concentrate the vital energy (prana) on the Anahata spiritual heart while the gaze of the eyes (drishti) directs the vital energy upward, toward the pineal gland. Heightened activity of the pineal gland prepares the brain and body for heightened states of spiritual awareness.

The “Flying Lotus”

Asanas keep the endocrine system balanced and help break through these destructive collective patterns of thought and feeling that degrade our humanity. By first balancing the lower glands, we must liberate the pineal gland that has been cognitively beseiged by egotistical thought contamination and materialistic mentality. With this liberation we release the pineal gland´s spiritual nectar (amrta) to bring happiness and spiritual awareness back into the world.

Only a small percentage of us have to break through the barriers of boorishness in order to create a novel spiritual pattern in the collective mind of the species. It is an idea similair to the “Hundredth Monkey” theory in which a few monkeys on a remote island discovered a new root to eat and then soon afterward other monkeys of the same species on other islands also discovered this new food. After a “hundred monkeys” or so discovered this and vibrated the collective mind of the species with this new pattern of information, the information percolated unconsciously to rest of the species and they adopted the behavior as second nature. Similarly, the human race could evolve if only some of us transform our animal human consciousness into spiritual human consciousness.

Yama And Niyama, Universal Ethics

How we see the physical world is determined by what level of mind we use to see it. Only in the lower levels of mind is cognitive activity dominated by the senses and cerebral activity. If we purify the Svadhistana, or conceptual level of mind and liberate it from narrow, egoistic thinking, then it is possible to see the world as a projection of thought. To know this is to change our thoughts and thus change our world. Here is where we realize something very deep about our essence and its connection with a higher, cosmic order that works through our evolving Self awareness, if we allow it to. With the six vrttis of the Svadhistana mind in balance, one can liberate oneself from self-exile and learn to trust that you have a place in the cosmic moral order.

The Svadhistana, Conceptual Mind is capable of abstract thought and therefore the idea of a self naturally arises. It is so important that this “self-establishing” mind be based on love, security, and rationality. Yama and Niyama are simple, yet profound guides for human conduct that foster spiritual awareness and union at all levels awareness and for human, “mind-preponderant,” “self-establishing” beings. The Svadhistana level of mind corresponds to the “liquid factor” of unified energy. This “liquid” energy is a unified field of waves that collapse and crystallize into the material world, the solid factor. The liquid factor is more a world of “waves” than a world of “particles.” Conceptual awareness is greater and we can comprehend our relationship with the natural and social worlds. This subtle, moral awareness is encompassed within these 10 universal principles. They help keep our external mental projections from reacting, from clashing and bouncing back against the real, living, conscious universe, which is the Macrocosmic Mind of Brahma. To go against the Tao, the cosmic order, will always cause reactions or deformations in the unified field of the liquid factor. The universe always re-adjusts itself from its deformations and we therefore are always experiencing our reactions. “As you think, so you become,”

Tantric yogis realized that in order for a human being to properly develop personally and socially to the degree where they are capable of practicing sadhana (meditation), it is necessary to have a moral code of conduct as a friendly guide. All societies teach norms and customs that ideally should help orient its members toward proper conduct so that there is harmony in that society. In contemporary society there is less and less wisdom that parents teach their children. The values people often learn through the media and in society in general teach superficiality, domination, selfishness, and materialism. Very few people have the notion that they live in a live universe where there really exist certain moral laws of harmony and balance. So often, those that speak of morality use it as a fearful force to control the behavior of others instead of using moral wisdom to free the mind from distorted ideas. Religious and ethical systems often give one a “rationale,” a pattern of how to behave. What they often lack is how to create the conditions to help one realize moral discernment. Yama and Niyama isn’t about being a good sheep that follows all of the rules like a cog in the system. This world is relative and there are no hard and fast, inviolable laws that apply to every person in every situation. The universality of Yama and Niyama consists in the openness of these concepts that the spirit of the idea pervades all possible situations. For example, ahimsa, the first and most important ethical principle of yama, is not absolute non-violence where the moral law says you can’t kill a mosquito or accidentally step on a bug. Instead, ahimsa is the spirit of not having violent intentions toward any entity. Ahimsa is an attitude that one carries into every situation, remembering that the Supreme Consciousness is behind all life. Perhaps this principle doesn’t give you the exact manner to respond to every given situation, but does suggest the spirit of interaction. If it did tell you exactly what to do, then what would be the value of discernment? What is important is that one understands violence in all aspects and sincerely tries to never inflict this unconscious destruction upon others. The basic idea of Yama and Niyama is that all beings are sentient and have an existential purpose. All beings need intelligent culture and compassionate nurture. All of the principles of Yama and Niyama lead to universal love. All beings are ultimately Shiva, but need a little care and nourishment to realize this. Yama and Niyama helps inspire this universal sentiment.

The 10 principles of Yama and Niyama are just and very universal spiritual values that are really applicable to all societies in that they are practical values based on dharma, based on our essential nature. The principles of Yama and Niyama would be the simple, natural goodness of a realized being, a Bodhisattva They give us a working model of morality, of how a sadhaka, or practitioner of sadhana should behave so as to protect their spirit. Their understanding helps the individual not just to adapt to society, but to help one understand the deep truth and purpose of morality. Yama and Niyama aren’t so much divine commandments as they are practical guides to conduct. For the Svadhistana mind to develop properly in a secure social environment and with self confidence, Yama and Niyama are indispensable. They keep the mind free of complexes generated by ignorant and selfish impulses that make sadhana impossible. What enforces and inspires morality isn’t the threat of punishment so much as the understanding of action and reaction. Good moral education cultivates the discerning intellect so that the physical desires aren’t just repressed but properly understood. When one sees that suffering and alienation are the result of selfish, unconscious actions, then one truly wants to find a path of activity that purifies and liberates instead of enslaving one to unwholesome desires. The 5 principles of Yama teach balance in social behavior, while the 5 principles of Niyama orient one toward basic spiritual discipline. They are as follows:

Yama: Social practices

-

Ahimsa: Not to inflict pain or hurt on anybody with intention by thought, word or action,

-

Satya: The benevolent use of mind and words with compassionate truthfulness.

-

Asteya: To renounce the desire to acquire the wealth or qualities of others.

-

Brahmacarya: To keep the mind always absorbed in Brahma and see all beings as Brahma’s expression.

-

Aparigraha: Live simply and avoid material excess.

Niyama: Personal practices

-

Shaoca: Purity of the body, mind, and environment.

-

Santos’a: Mental equipoise and peace of mind.

-

Tapah: To undergo hardship for the welfare of others through selfless service.

-

Sva’dhya’ya: The study and proper understanding of spiritual scriptures and philosophical books.

-

Iishvara pran’idha’na: To take shelter or meditate on Iishvara, the Supreme Consciousness.

Excerpt from A Name To The Nameless

For a more complete and very lucid, modern and socially applicable understanding of Yama and Niyama, I refer the reader to the book of Ananadamurti, “A Guide To Human Conduct.”